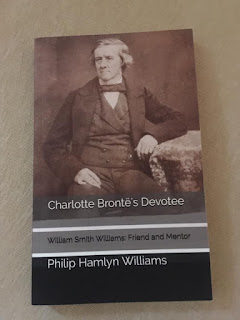

“The mysterious publisher William Smith Williams has always been the unsung hero of the Brontë Story. Not only did he discover Jane Eyre, he was Charlotte Brontë’s friend and supporter. In a fascinating book Smith Williams is at last brought to life thanks to the forensic skills of his great, great nephew.”

Biographer, Rebecca Fraser, kindly wrote this on reading the draft of the book I had been working on for the last fourteen years and on which I had the pleasure of speak to the open meeting of the Civic Trust on 29 November 2019.

The book tells story of Charlotte Brontë’s relationship with William Smith Williams who, as the Reader at her publisher Smith, Elder & Co, recognised her genius. But, who was he? William was a radical Victorian, friend to many of the giants of 19th century art and literature: Thackeray, Thomas Carlyle, Elizabeth Gaskell, George Eliot and the Rossettis. Through him we gain an insight into the world of publishing, the art and science of lithography and the controversial thinking of John Ruskin on women’s education, politics and economics. He was a family man and, with his wife Margaret, produced a line of remarkable progeny.

Whence had he come and wither did he go? Charles Dickens and George Meredith were also publishers’ Readers and their stories are well known, but what of William Smith Williams?

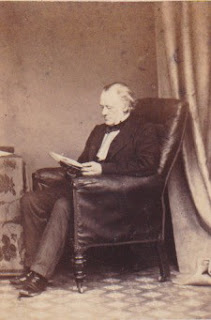

I found a true Renaissance man as at home with art as with literature, with science as with politics. His childhood had been spent in the crowded courts bordering London’s Strand. He was orphaned at age fourteen and then largely self educated. He was an apprentice publisher and then a lithographer before joining Smith, Elder. He wrote a poem in praise of John Keats and presented a paper to the Society of Arts on Lithography. Following his all too few years of friendship with Charlotte Bronte, he mentored many other writers. One such, Frederick Wicks, wrote this if him:

‘Thrusting back his massive growth of white hair, he would clasp his hands nervously in thought before delivering his opinion, and then would follow in short, pregnant sentences a perfect flood of light upon the matter in hand. He was never content with general commendation and approval, but always gave good, sound reasons and sufficient cause for all he thought. Among the many pregnant phrases that fell to my lot was one of extraordinary value as a check to the exuberance of youth. “You need,” he said, “restraint – not that which checks, but that which guides the literary faculty.”’

He edited the 1861 Selections of the Writings of John Ruskin and then supported Ruskin in the publication of his works on political economy. Of interest to the citizens of Lincoln is a letter John Ruskin wrote to the then Mayor, WT Page, on 22 January 1883 the original of which is in the Lincolnshire Archives. We all know what Ruskin said about Lincoln Cathedral; well, it is in this letter:

‘I have always held (and am prepared against all comers to maintain my holding) that the Cathedral of Lincoln is out and out the most precious piece of architecture in the British islands, and—roughly—worth any two other cathedrals we have got.’

He said rather more which may make us shudder:

‘The town of Lincoln is a lovely old English town, and I hope the Mayor and Common Council men won’t let any of it (not so much as a house corner) be pulled down to build an Institution or a Market—or a Penitentiary or a Gunpowder and Dynamite Mill—or a College—or a Gaol—or a Barracks—or any other modern luxury.’

But also set a challenge:

‘It might possibly make the upper students of the art classes look up a good many things that they would be the better for knowing, if the Town Council were to offer a prize for a design to be painted or frescoed in the Town Hall, of the most pathetic and significant scene in all British history—the first real “Union of Scotland and England”—in the funeral procession of Bishop Hugh—when the King of England (John), barefoot, bore the coffin, with three Archbishops, and the King of Scotland followed, weeping. The prize might be open to all students born between Lincoln and Holy Isle?—or better, perhaps, between Tweed and Trent?’

William Smith Williams was buried in Kensal Green cemetery with his wife, one son and two daughters and son in law celebrated portrait painter, Cato Lowes Dickinson under a memorial designed by AC Gill. His daughter, Anna, was a celebrated concert soprano. One grandson, Sir Arthur Lowes Dickinson, was a founding partner of Price Waterhouse in the USA, another, Goldie Lowes Dickinson, was one of the thinkers behind the League of Nations.

Charlotte Brontë’s Devotee may be found at Lindum Books on Bailgate.

This article is reproduced from the Civic Trust annual report

%20copy.jpg)